Anatomy and reason for

The global community is being called upon to respond to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in a variety of different ways, including through health, security, economy, education, and employment. Wuhan, China was the birthplace of the deadly virus that quickly swept across the globe. The global COVID-19 pandemic was significantly tempered by the widespread demonstrations of solidarity and cooperation that took place at the time. As an act of international solidarity, countries gathered their top researchers and innovators to share insights on cutting-edge topics and collaborate on projects to spread information and increase people’s agency in their communities. The researchers in this study set out to determine how the global COVID-19 pandemic has affected various sectors of the Saudi population. We also aimed to gauge how the Saudi public at large views the pandemic’s immediate and long-term consequences.

Methodology

Subjects for this cross-sectional study were recruited from all over the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia between March 2020 and February 2021. The 920 responses came from a self-developed online survey that was sent out to thousands of people in the Saudi community.

Results

About 49% of the people who participated in the study put off visits to the dentist or cosmetic surgeon, and 31% put off routine checkups at the doctor’s office or local clinic. As much as 64% of Muslims say they never or rarely hear the “Tarawih/Qiyam” prayers. In addition, 38% of people in the study reported feeling anxious and stressed, 23% reported having sleeping disorders, and 16% wanted to isolate themselves from society. On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic encouraged about 65% of the people in the study to stop eating out. Sixty-three percent of them also said they had learned something new during the pandemic. The majority of respondents (54%) predicted economic hardships in the wake of the curfew recession, and nearly half (44%).

Conclusion

Individuals and communities alike in Saudi Arabia have felt the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Negative mental health, financial difficulties, difficulties with homeschooling and working from home, and an inability to meet spiritual needs were all cited as short-term effects. One positive aspect of the community’s response to the pandemic was the members’ willingness to learn and grow.

Introduction

The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was first detected in Wuhan, China, but has since spread to other parts of the world due to its high rate of transmission [1]. Within nearly two months of the first reported case, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic [2], with more than 213 countries around the world experiencing outbreaks. The health, security, economy, education, and employment sectors, among others, across the globe, were put to the test in the face of this pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had significant societal and economic effects. The ability to work remotely has helped many people, both professionally and financially. However, employees with lower wages and fewer skills have been hit harder by the pandemic because their limited abilities mean they are more likely to experience high turnover and unfavourable working conditions. Education has also been impacted by the pandemic, with many institutions switching to online delivery in response. Lack of on-campus activities had a negative impact on students’ ability to work together on group projects, discuss technical and financial issues, and resolve crises quickly. During the pandemic curfew, all of these issues were encountered by students attempting to learn online [4]. Stress, anxiety, depression, insomnia, denial, anger, and fear were just some of the mental health issues people were dealing with [5].

The Saudi government, represented by its authorities, invested heavily in monitoring the COVID-19 situation through social distancing measures and mass gatherings’ risk assessment, implementing measures such as suspending Umrah seasons, shifting to “from a distance” learning and work platforms, cancelling a number of sports, cultural, and entertaining events for the first time in decades.

Pandemics place communities under intense pressure, which has the potential to negatively impact people’s health. Recent research has shown that the recommended preventative measures for COVID-19, such as self-isolation and home quarantine, can have negative effects on mental health [7]. Many patients who have recovered from COVID-19 have developed persistent symptoms of depression and anxiety, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis [8]. A psychological conundrum, unexplored to this point, emerged as a result of the lockdown, curfew law, and fear of infection. Studies have reported a range of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, insomnia, denial, anger, and fear, in those exposed to COVID-19 [5].

Reducing the likelihood of contracting and spreading an infection or disease from person to person is one of the primary functions of social distance [9]. In addition, Mediterranean people value greetings highly as a means of initiating contact and starting conversations [10,11]. Handshakes, kisses on both cheeks, and even hugs are all part of the close contact required [10]. Additionally, research has shown that Arabs maintain a closer personal distance during their communications, to the point where it can be unsettling to Westerners [12]. Accordingly, it was difficult for people from the Saudi culture to adapt to the new distancing measures [6,13] because the cultural norm is characterised by the prevalence of strong family ties and frequent social gatherings.

Observing religious rites is central to Saudi culture. The two holiest places in all of Islam are both located in Saudi Arabia (i.e., Mecca and Medina). Religion and religious observance play an essential role in the daily lives of Saudi citizens. On March 4th, the government of the Kingdom announced that all citizens and permanent residents would be banned from performing the Umrah pilgrimage for an unspecified amount of time. For the first time in decades, and despite the potential economic and political consequences, the “Umrah” pilgrimage to the Holy Mosque in Mecca was suspended as a precautionary measure to combat the virus. In light of this, the Saudi community had to work hard mentally and emotionally to overcome the spiritual and social tests that arose during the holy months of Ramadan and Eid [6].

Also Read : Magnificent vegan lifestyle in seven UK cities

The researchers in this study set out to determine how the global COVID-19 pandemic has affected various sectors of the Saudi population. We also aimed to gauge how the Saudi public at large views the pandemic’s immediate and long-term consequences.

Substances & Techniques

Subjects for this cross-sectional study were recruited from all over the Kingdom between March 2020 and February 2021. The total number of people in Saudi Arabia was estimated at 34,218,169 for the 2019 national census [14], so a simple random sample was drawn from this pool. Sample sizes were determined using OpenEpi 3 [15].

Each and every Saudi Arabian resident over the age of 15 was considered. No one under the age of 15 was allowed to participate, and neither Saudis nor non-Saudis who were not permanently residing in Saudi Arabia were either.

The survey was designed using SurveyMonkey [16] by Momentive Inc. in Waterford, New York. It was divided into four parts with a total of 23 questions (both open- and closed-ended), probing topics like demographics and the impact of the crisis on faith, finances, health, and outlook. Both the Arabic and English versions of these questions featured branching logic in an effort to reduce the survey’s overall length. Following an explanation of the study’s goals and any relevant ethical considerations, participants gave their informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at Alfaisal University gave their blessing to this research (IRB: 20035).

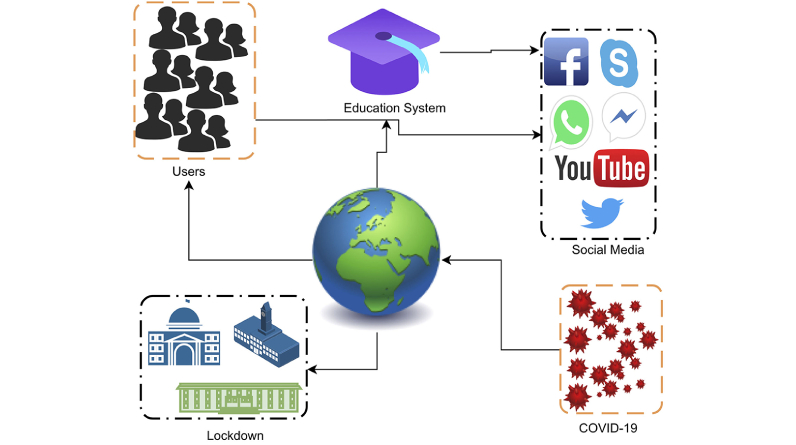

In May 2020, before the curfew was lifted, the self-created online questionnaire was distributed to members of the Saudi community via social media (WhatsApp, Twitter, and Snapchat). Before the questionnaire was made available to the general public, it was tested on a smaller group of 20 people, 10 of whom spoke each of the two languages (Arabic and English). Participants were offered the chance to win one of ten randomly selected gift vouchers as an incentive to fill out the survey.